Making friends with the boys

Julien Baker, Phoebe Bridgers, and Lucy Dacus gave us everything they got at the PNE Amphitheatre in Vancouver. We became part of their story; it was the time of our lives.

The air tastes better in Vancouver.

Tracing circles around Stanley Park is exhilarating. It is peaceful; it is crowded. The park is the kind of public space you love to get lost in, which is a given when you take forever to realize the Seawall is a one-way ride for bikes and you completely miss the totem poles on your first lap, like I did. The wrong turn is worth it, though, because after you finish that second lap (for good measure), return the bike you rented, and walk off the glute pain, you stumble upon a hole in the wall serving some of the best ramen you ever had.

The final week of my July vacation was more solitary than my jaunt in Montréal, with no Jon to lead me on adventures and no serendipitous parties with left-wing journalists and organizers to carry me late into the night. Unlike Montréal, I spent a week in Vancouver for a very specific purpose: to see Boygenius.

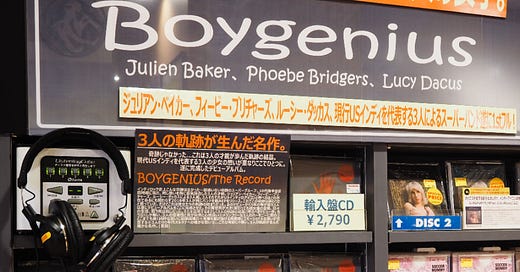

Boygenius is a superband. Three best friends—Julien Baker, Phoebe Bridgers, and Lucy Dacus, who all have their own successful solo careers—have collaborated for a second time to bless the world with alternative-indie-folk-rock-n-roll tracks as only a trio of queer 27-year-old women can.

Boygenius projects real-world, in-your-face lyrics on beams of supernatural, emotive motifs. Each band member excels at this when they make their own music, and the effect increases exponentially when the three team up to write songs together. Take this example from the underrated Anti-Curse, where Julien spins a story of self-doubt and restless love through slice-of-life turned allegory:

Gettin’ deep I’m out of my depth at a public beach I never listened, I had to see for myself It’s comin’ in waves Shoots through my mind like a pinball strayed Friendly fire, point-blank Salt in my lungs Holdin’ my breath Makin’ peace with my inevitable death

All things considered, I hope Julien enjoyed the Vancouver ocean and solitude like I did. This is songwriting fans fall in love with and puts Boygenius a step or two above more mainstream artists like Taylor Swift (who Phoebe opened for earlier in the Eras tour). Julien, Phoebe, and Lucy write relatable, expressive, cathartic music, just like Taylor, but the boys’ metaphors are smarter, their cuts, deeper—not that that’s an impossible test to pass.

Boygenius asks, “Will you be a satanist with me? Will you be an anarchist with me? Will you be a nihilist with me?” They do not demand answers to these questions, but you are enjoined to wonder, to meditate on them and let them drag you under. Whether or not you’ve scored some off-brand ecstasy, there’s nothing as euphoric as screaming “Sleep in cars and kill the bourgeoisie!” alongside thousands of fellow superfans. (This may be one reason Julien says Satanist is her surprise favourite song to shred live.)

The fans listen to Boygenius the same way we listen to the band’s individual members, which is to say we do much more than listen to them: we love them, we live for them, we would die for them. Phoebe is mother. Lucy is literally perfect. Julien makes you question… everything. We worship Boygenius and they bask in our collective radiance, but they do not take themselves too seriously and they do not let fame change them.

Boygenius’ relationship with themselves seems healthy even if our relationship with them is not. Every track on their new album feels as if Julien, Phoebe, and Lucy wrote them for each other. The Boygenius project would thrive if they were the only three women in the entire world and beyond; the legions of fans are a happy coincidence, a little bonus that found its way along for the show.

In fact, the boys were bold enough to open their 2018 debut EP with a song—Bite The Hand—about fans and the unhealthy, parasocial obsession many form with the band members, something else they share with Swift. From Bite The Hand:

I can’t hear you You’re too far away I can’t see you The light is in my face I can’t touch you I wouldn’t if I could I can’t love you how you want me to … Maybe I’m afraid of you I’ll bite the hand that feeds me

A caustic, unrestrained message that countless other music fans would benefit hearing from their favourite artists. Boygenius turned the cameras on us when they played Bite The Hand during our concert, covering their backing screen with panning overheads and closeups of all 7,000 of us, and all 7,000 of us screamed in joy as if we weren’t the subject of their critique. I wonder how many sang along in ignorance of the irony.

Boygenius cannot escape this dynamic, however. Every chord and melody plants parallels with and seeds outright sequels to the band’s previous work and, more than that, their lives. The record is a bountiful harvest for die-hard fans who compulsively research and piece together the connections Boygenius leaves for us.

Boygenius does not force this phenomena. It feels natural. Julien, Phoebe, and Lucy are simply growing up and writing songs about their experiences, as most artists do. For us, each chorus has the potential to change everything we thought we knew about who they are and what they’ve been through, but the band is not performing for us, they are performing for them.

Lucy winds two songs together—True Blue and Leonard Cohen—with a single, deliberate call and response:

And it feels so good To be known so well I can’t hide from you Like I hide from myself I remember who I am When I’m with you***Tellin’ stories we wouldn’t Tell anyone else You said,“I might like you less “Now that you know me so well,”

Boygenius released three singles to soft-launch the record, each spearheaded by a member of the trio: $20 (Julien); Emily, I’m Sorry (Phoebe); and True Blue (Lucy). One day later, I burst into a co-worker’s office to ask which they liked most. I had fallen for the tortured, nostalgic Emily, I’m Sorry and rocked out to $20 during my daily commutes, but my pal said they preferred True Blue, and I think I can see why.

True Blue sounds romantic, but it is really about platonic love, like nearly every song on the record. Lucy gives voice to the affection you can only have with your best friend—who, I suppose, can’t necessarily not be your romantic interest, but that isn’t the point—and the short and sweet Leonard Cohen explores the practical implications of True Blue’s heady themes.

Cohen alludes to the vulnerability and anxiety that accompanies True Blue triumphs, the terrifying “I might like you less now,” that threatens us when we know, and are known, so well. Nevertheless, Lucy encourages us to push through the dread, to nurture our relationships, to embrace our friends even if letting them closer feels like a risk. After all, “There’s a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in.”

Leonard Cohen shares imagery with another Lucy vocal in Not Strong Enough, the record’s most popular song by far. From Cohen:

On the on-ramp you said,

“If you love me you will listen to this song,”

And I could tell you were serious, so I

Didn’t tell you you were driving the wrong way

On the interstate until the song was done

Literal, lean storytelling, this time about a night out with Phoebe. Lucy evokes a scene that happens all the time in relationships, sure, but also just as likely with a best friend, a confidant, the only person you might trust more than your partner.

But we are not always surrounded by trust and love, are we? As promised, from Not Strong Enough’s denouement, Lucy sings:

Coming to in the front seat

Nearly empty

Skip the exit to our old street

And go home

Go home alone

Lucy carries the album with rich, underappreciated harmonies. It is satisfying to hear her subtle storytelling and expert pen shine on the songs that are so clearly hers.

Letter to an Old Poet, the last track on the record, is a breathtaking and rare example of a musician creating a direct sequel to their own work. It is a Phoebe Bridgers song, unmistakably, but it does not sound like the rest of the record. Something about it does not fit. Poet is not about Julien or Lucy. Phoebe is writing a letter to herself, for herself, and the power of friendship has given her the strength to crush this album’s finale in the most personal way.

An intimate melody awakens. It sounds like Me and My Dog from the band’s self-titled EP, but instead of riding out on a banjo the notes dance on keys and have become, like Phoebe, muted and melancholy. Letter to an Old Poet swells, once again mirroring Me and My Dog. In 2018, Phoebe sang with more angst and defiance. In that climax, she and Julien belt out:

I want to be

Emaciated

I want to hear one song

Without thinking of you

It’s different this time. Phoebe sets us up with the same chords for the same release, but instead she breaks through an emotional dam we did not expect to burst. Poet pauses, then crashes down in a devastating wave:

I want to be

… Happy

I’m ready

To walk into my room

Without looking for you

Everything rushes out into the open. It’s optimism. It’s an affirmation. The undeniable energy flowing throughout the album—sometimes revelatory, other times holding its breath, like our three heroines—is free, and that same keyboard melody plays on just as we are meant to play on.

I cannot overstate how powerful this moment is, especially for longtime fans who have screamed along to Me and My Dog again and again for the last five years. I stopped dead the first time I listened to Poet. “… Happy” struck like metal and stole my breath. But the chord progression was an old friend, one that brought me right back to an emotional edge, and then, instead of sharing in what I thought was pain and emaciation, Boygenius invited me to share in hope, in growth, in tomorrow and togetherness.

By now the sun had set on Vancouver, but Boygenius was there to tell us that, whatever our problems and whatever our own old poets wrote about, the sun will rise again, and once it does it will shine all the brighter.

Friendship, platonic intimacy, elation—this is the record. Julien, Phoebe, and Lucy can be hard to read, so I will not pretend to fully understand everything they tried, and did not try, to get across in their first full-length album as a superband. But the celebration of friendship is there for everyone to experience. It is explicit in the lyrics and it is obvious in the production. They made this album together, with each other and for each other.

I saw Boygenius with an old friend, Kelsey, who I met at university a decade ago. She had never listened to the band before that night, but just as Julien finished her final guitar solo she turned and told me the concert changed her life. I think Boygenius changed my life, too. Short of that, I’m going to call old friends more often from now on, which is just as well.